A sound alternative

Investigating the affect of sound visualisations on deaf gamers' experience of mood in videogames

Overview

This project explored alternatives to traditional captions as an accessibility provision for deaf gamers, focusing on sound visualisations and their ability to convey not just information, but mood and emotional context within videogames.

Drawing on the work of Richard van Tol, Donald Norman, Michel Chion, and Kristine Jørgensen, this project examined whether sound visualisations could provide a more affective and inclusive alternative to traditional captions in videogames.

While captions are widely accepted as the default solution for deaf and hard of hearing players, they primarily support basic usability. Sound in games, however, plays a much richer role: shaping atmosphere, supporting spatial awareness, and guiding emotional response. This research asked whether visual representations of sound could better fulfil those roles, while remaining inclusive for both deaf and hearing players.

The project took the form of a research-led design investigation, combining literature review, questionnaires, and the design and evaluation of an interactive game prototype featuring three different sound-representation systems.

My approach

I approached this project as both a design researcher and accessibility advocate, grounding practical experimentation in theory while centering lived experience and inclusion.

Research framing

I began with an extensive literature review to understand:

the functional and emotional role of sound in games

limitations of captions as an accessibility tool

theories of affect and emotional design

principles of universal and inclusive game design

This theoretical grounding helped ensure the work addressed accessibility as a design opportunity, not a compensatory add-on.

Understanding player perspectives

To avoid designing in isolation, I gathered qualitative and quantitative data through self-completion questionnaires distributed across mainstream and deaf-focused gaming communities.

These explored:

gaming habits and preferred genres

experiences of captions and subtitles

attitudes towards accessibility features

perceptions of intrusiveness and immersion

This stage was essential in revealing that accessibility systems are not only used by deaf players, but also by hearing players in noisy environments, shared spaces, or when playing without audio.

Designing and testing alternatives

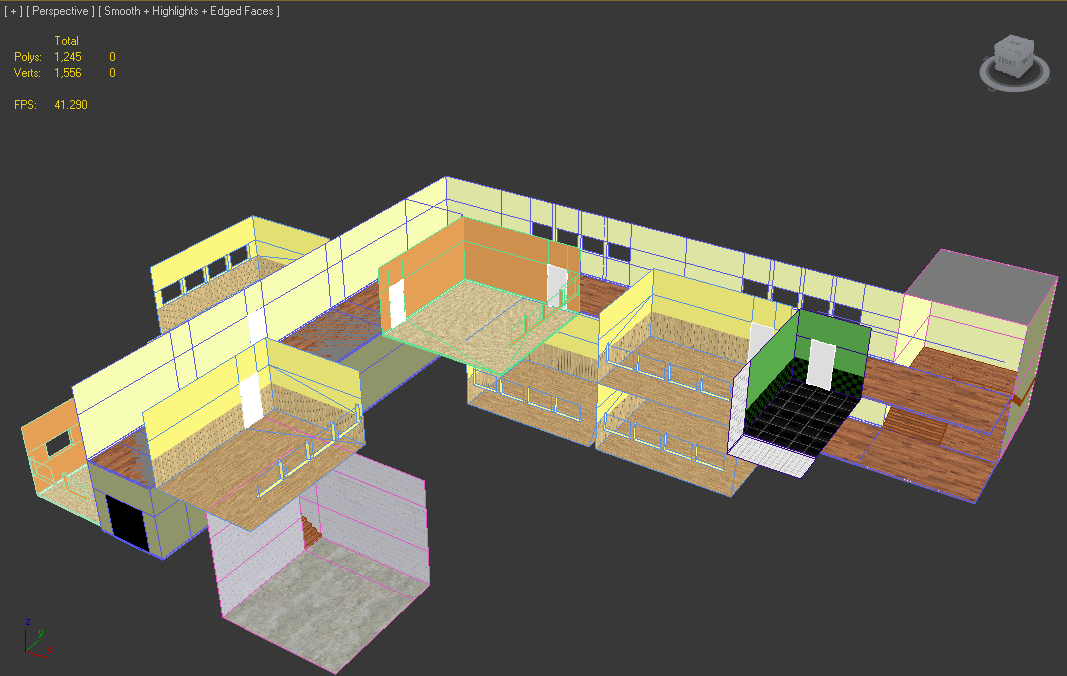

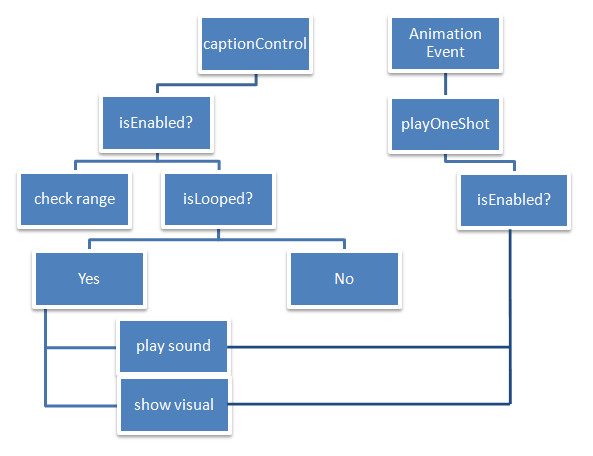

I then designed and built a small first-person stealth game prototype using Unity, implemented in three versions:

Traditional captions

Symbolic sound visualisations

Combined visual systems (symbols plus text elements)

Each version was tested by players, who completed structured questionnaires after use. This allowed direct comparison of usability, emotional impact, and perceived intrusiveness across the three approaches.

What I delivered

A structured, research-led approach to evaluating accessibility systems in games

Online questionnaires and consent processes

A playable Unity game prototype with three accessibility variants

Comparative usability and affective evaluation of sound representations

Thematic analysis of player feedback

A final dissertation synthesising theory, design, and user insight

Impact

The findings challenged the assumption that captions are always the best or only solution for deaf gamers.

Key outcomes included:

Symbolic sound visualisations were consistently preferred over captions by both deaf and hearing players

Players found sound visualisations more immersive and better integrated into the game world

Symbolic visuals were more effective at conveying mood and tension

Captions were often described as spatially ambiguous and emotionally flat

Combined systems improved awareness but were perceived as visually intrusive

Notably, several players commented that the symbolic visualisations felt like a natural part of the game’s design, rather than an accessibility feature — a strong endorsement of inclusive, universal design principles.

Reflection

This project was formative in shaping my approach to accessibility as a design discipline. It reinforced that accessible solutions should not merely replicate information in another format, but consider experience, emotion, and identity.

I learned the value of:

designing with communities rather than for them

testing assumptions about “standard” accessibility patterns

balancing clarity with immersion

treating accessibility as a creative, system-level challenge

I encountered some pushback from parts of the gaming community, particularly around the expectation that researchers should establish trust and presence within a community before asking people to participate in research.

This was a valuable reminder of the long history of exploitative research involving disabled communities. I attempted to mitigate this by being transparent about my aims, methods, and intended outcomes, but the experience reinforced the importance of working with existing communities over time, rather than approaching them only at the point of data collection.

The work also highlighted the risk of accessibility features becoming visually dominant or stigmatising when poorly integrated. Designing accessibility that feels intentional, elegant, and shared by all users remains a guiding principle in my practice.

Overall, this project deepened my commitment to inclusive design approaches that benefit everyone — not by simplifying experiences, but by enriching them.

Gallery